Agent Builder is available now GA. Get started with an Elastic Cloud Trial, and check out the documentation for Agent Builder here.

With that (fairly extensive) background on the ways LLMs have changed the underlying processes of information retrieval, let’s see how they’ve also changed the way we query for data.

A new way of interacting with data

Generative (genAI) and agentic AI do things differently than traditional search. Whereas the way we used to begin researching information was a search (“let me Google that…”), the initiating action for both gen AI and Agents is usually through natural language entered into a chat interface. The chat interface is a discussion with an LLM that uses its semantic understanding to turn our question into a distilled answer, a summarized response seemingly coming from an oracle that has a broad knowledge of all kinds of information. What really sells it is the LLM’s ability to generate coherent, thoughtful sentences that string together the bits of knowledge it surfaces — even when it’s inaccurate or totally hallucinated, there’s a truthiness to it.

That old search bar we’ve been so used to interacting with can be thought of as the RAG engine we used when we ourselves were the reasoning agent. Now, even Internet search engines are turning our well-worn “hunt and peck” lexical search experience into AI-driven overviews that answer the query with a summary of the results, helping users avoid the need to click through and evaluate individual results themselves.

Generative AI & RAG

Generative AI tries to use its semantic understanding of the world to parse the subjective intention stated through a chat request, and then uses its inference abilities to create an expert answer on the fly. There are several parts to a generative AI interaction: it starts with the user’s input/query, previous conversations in the chat session can be used as additional context, and the instructional prompt that tells the LLM how to reason and what procedures to follow in constructing the response. Prompts have evolved from simple "explain this to me like I am a five-year-old” type of guidance to complete breakdowns for how to process requests. These breakdowns often include distinct sections describing details of the AI’s persona/role, pre-generation reasoning/internal thought process, objective criteria, constraints, output format, audience, as well as examples to help demonstrate the expected results.

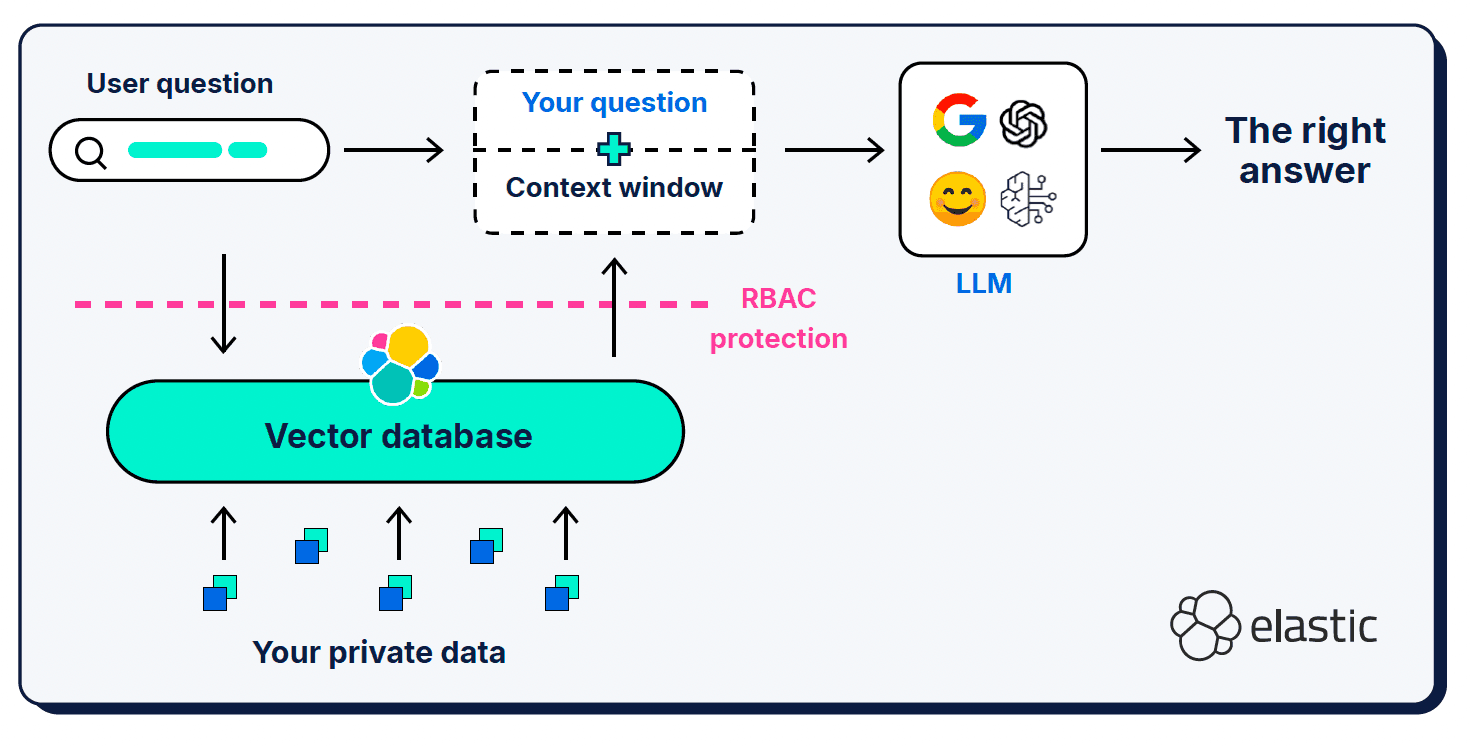

In addition to the user’s query and the system prompt, retrieval augmented generation (RAG) provides additional contextual information in what’s called a “context window.” RAG has been a critical addition to the architecture; it’s what we use to inform the LLM about the missing pieces in its semantic understanding of the world.

Context windows can be kind of persnickety in terms of what, where, and how much you give them. Which context gets selected is very important, of course, but the signal-to-noise ratio of the provided context also matters, as well as the length of the window.

Too little information

Providing too little information in a query, prompt, or context window can lead to hallucinations because the LLM can’t accurately determine the correct semantic context to generate a response from. There are also issues with the vector similarity of document chunk sizes — a short, simple question may not semantically align with the rich, detailed documents found in our vectorized knowledge bases. Query expansion techniques such as Hypothetical Document Embeddings (HyDE) have been developed that use LLMs to generate a hypothetical answer that is richer and more expressive than the short query. The danger here, of course, is that the hypothetical document is itself a hallucination that takes the LLM even farther astray from the correct context.

Too much information

Just like it does to us humans, too much information in a context window can overwhelm and confuse an LLM about what the important parts are supposed to be. Context overflow (or “context rot”) affects the quality and performance of generative AI operations; it greatly impacts the LLM’s “attention budget” (its working memory) and dilutes relevance across many competing tokens. The concept of “context rot” also includes the observation that LLMs tend to have a positional bias — they prefer the content at the beginning or end of a context window over content in the middle section.

Distracting or conflicting information

The larger a context window gets, the more chance there is that it might include superfluous or conflicting information that can serve to distract the LLM from selecting and processing the correct context. In some ways, it becomes a problem of garbage in/garbage out: just dumping a set of document results into a context window gives the LLM a lot of information to chew on (potentially too much), but depending on how the context was selected there is a greater possibility for conflicting or irrelevant information seeping in.

Agentic AI

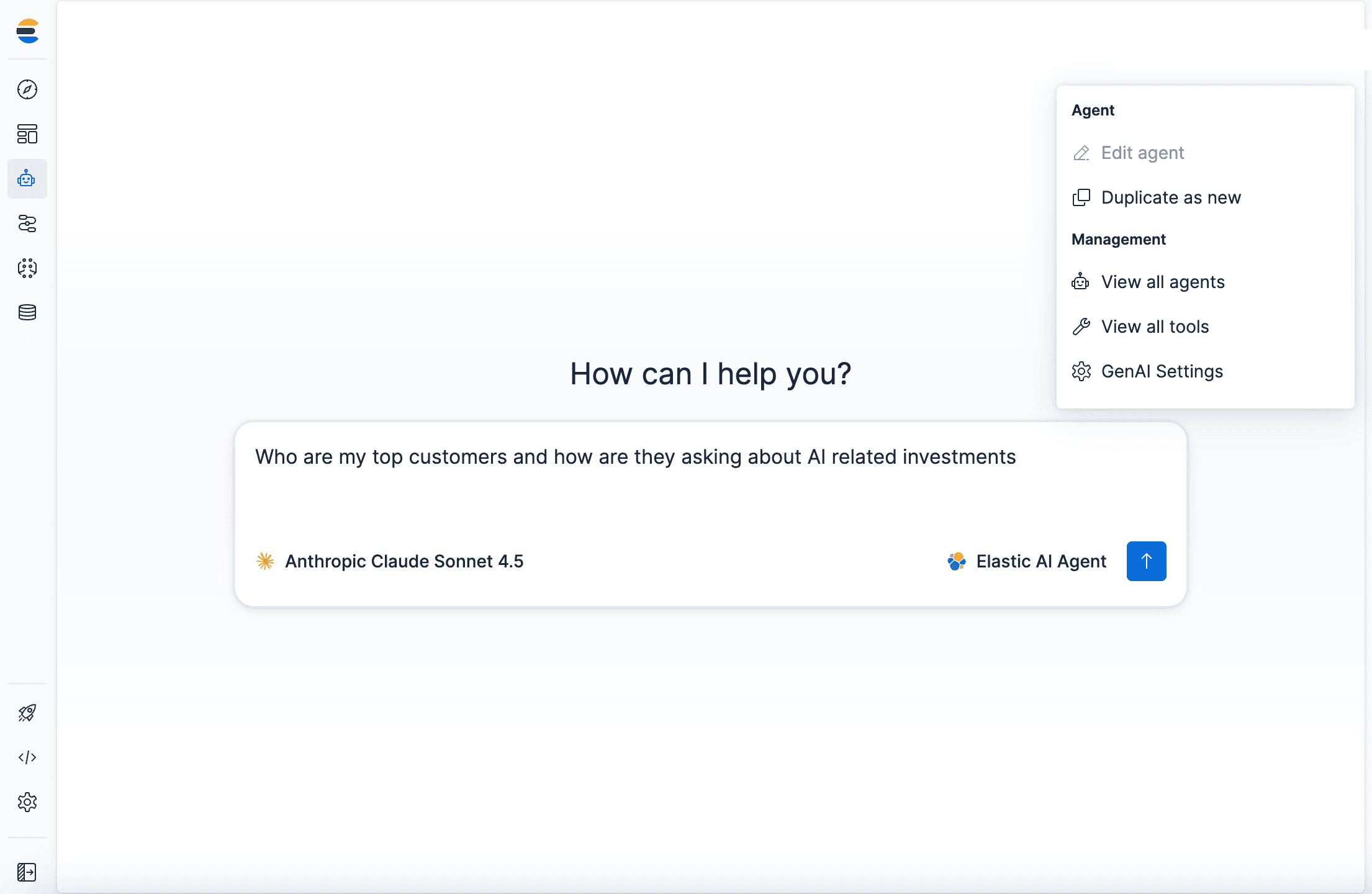

I told you there was a lot of ground to cover, but we did it — we’re finally talking about agentic AI topics! Agentic AI is a very exciting new usage of LLM chat interfaces that expands on generative AI’s (can we call it “legacy” already?) ability to synthesize responses based on its own knowledge and contextual information you provide. As generative AI became more mature, we realized there was a certain level of tasking and automation we could have LLMs perform, initially relegated to tedious low-risk activities that can easily be checked/validated by a human. Over a short period of time, that initial scope grew: an LLM chat window can now be the spark that sends an AI agent off to autonomously plan, execute, and iteratively evaluate and adapt its plan to achieve its specified goal. Agents have access to their LLMs’ own reasoning, the chat history and thinking memory (such as it is), and they also have specific tools made available that they can utilize towards that goal. We’re also now seeing architectures that allow a top-level agent to function as the orchestrator of multiple sub-agents, each with their own logic chains, instruction sets, context, and tools.

Agents are the entry point to a mostly automated workflow: they’re self-directed in that they are able to chat with a user and then use ‘logic’ to determine what tools it has available to help answer the user’s question. Tools are usually considered passive as compared to agents and built to do one type of task. The types of tasks a tool could perform are kind of limitless (which is really exciting!) but a primary task tools perform is to gather contextual information for an agent to consider in executing its workflow.

As a technology, agentic AI is still in its infancy and prone to the LLM equivalent of attention deficit disorder — it easily forgets what it was asked to do, and often runs off to do other things that weren’t part of the brief at all. Underneath the apparent magic, the “reasoning” abilities of LLMs are still based on predicting the next most likely token in a sequence. For reasoning (or someday, artificial general intelligence (AGI)) to become reliable and trustworthy, we need to be able to verify that when given the correct, most up-to-date information that they will reason through the way we expect them to (and perhaps give us that little extra bit more that we might not have thought of ourselves). For that to happen, agentic architectures will need the ability to communicate clearly (protocols), to adhere to the workflows and constraints we give them (guardrails), to remember where they are in a task (state), manage their available memory space, and validate their responses are accurate and meet the task criteria.

Talk to me in a language I can understand

As is common in new areas of development (especially so in the world of LLMs), there were initially quite a few approaches for agent-to-tool communications, but they quickly converged on the Model Context Protocol (MCP) as the de facto standard. The definition of Model Context Protocol is truly in the name - it’s the protocol a model uses to request and receive contextual information. MCP acts as a universal adapter for LLM agents to connect to external tools and data sources; it simplifies and standardizes the APIs so that different LLM frameworks and tools can easily interoperate. That makes MCP a kind of pivot point between the orchestration logic and system prompts given to an agent to perform autonomously in the service of its goals, and the operations sent to tools to perform in a more isolated fashion (isolated at least with regards to the initiating agent).

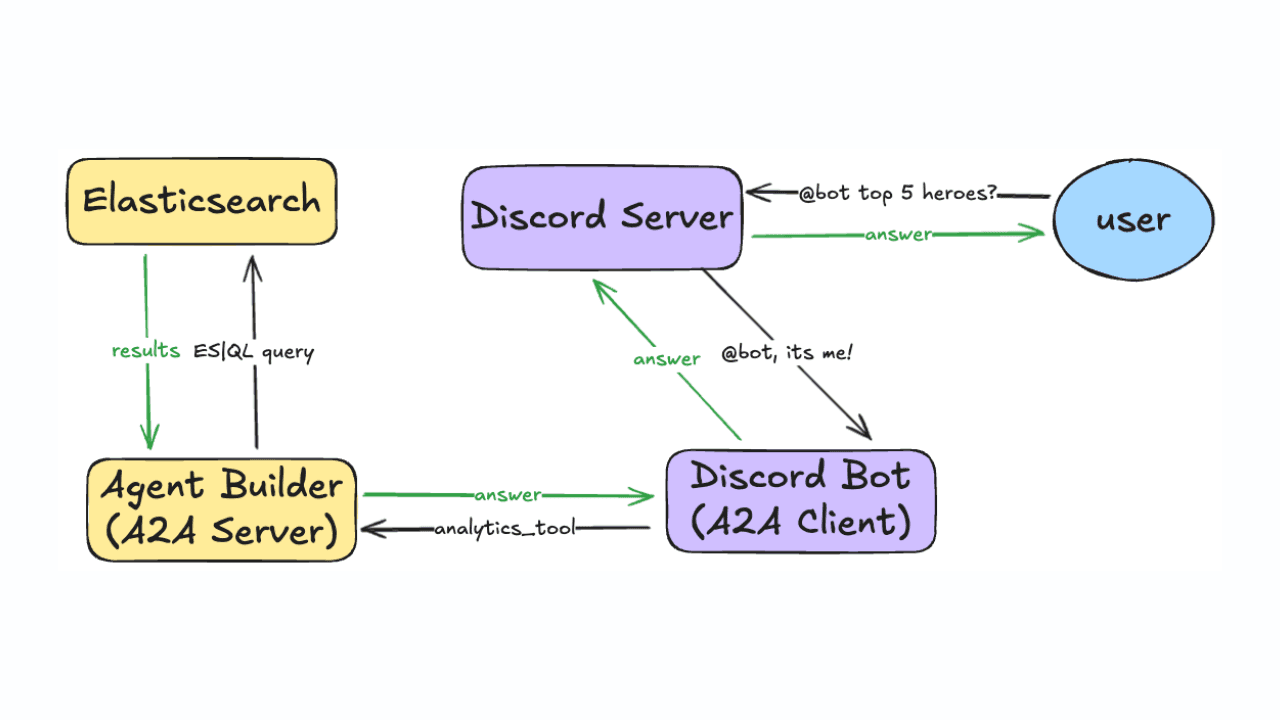

This ecosystem is all so new that every direction of expansion feels like a new frontier. We have similar protocols for agent-to-agent interactions (Agent2Agent (A2A) natch!) as well as other projects for improving agent reasoning memory (ReasoningBank), for selecting the best MCP server for the job at hand (RAG-MCP), and using semantic analysis such as zero-shot classification and pattern detection on input and output as Guardrails to control what an agent is allowed to operate on.

You might have noticed that the underlying intent of each of these projects is to improve the quality and control of the information returned to an agent/genAI context window? While the agentic AI ecosystem continues to develop the ability to handle that contextual information better (to control, manage, and operate on it), there will always be the need to retrieve the most relevant contextual information as the grist for the agent to mill on.

Welcome to context engineering!

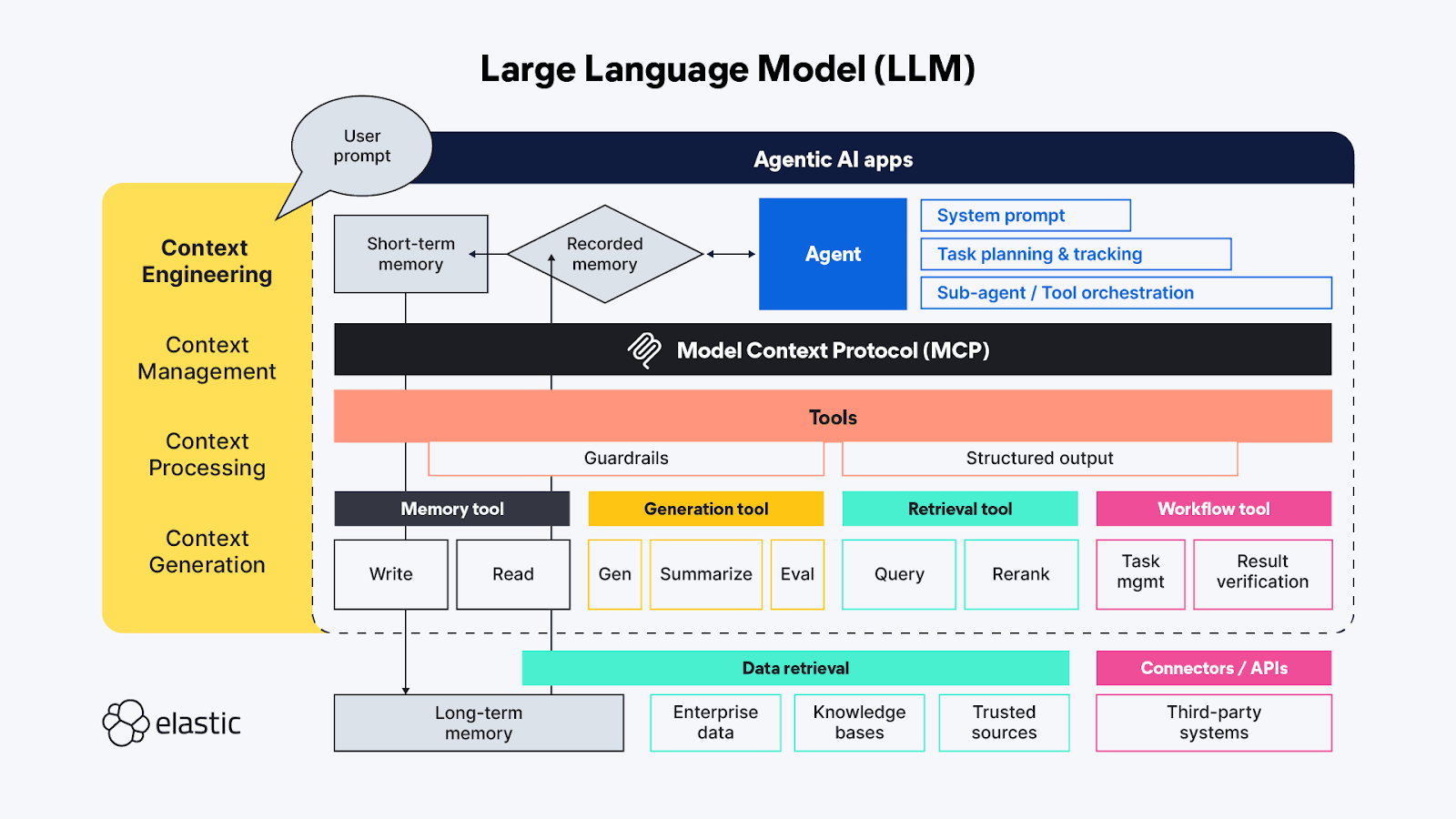

If you’re familiar with generative AI terms, you’ve probably heard of ‘prompt engineering’ - at this point, it’s almost a pseudo-science of its own. Prompt engineering is used to find the best and most efficient ways of proactively describing the behaviors you want the LLM to use in generating its response. ‘Context engineering’ extends ‘prompt engineering’ techniques beyond the agent side to also cover available context sources and systems on the tools side of the MCP protocol, and includes the broad topics of context management, processing, and generation:

- Context management - Related to maintaining state and context efficiency across long-running and/or more complex agentic workflows. Iterative planning, tracking, and orchestration of tasks and tool calling to accomplish the agent’s goals. Due to the limited “attention budget” agents have to work within, context management is largely concerned with techniques that help refine the context window to capture both the fullest scope and the most important bits of context (its precision versus recall!). Techniques include compression, summarization, and persisting context from previous steps or tool calls to make room in working memory for additional context in subsequent steps.

- Context processing - The logical and hopefully mostly programmatic steps to integrate, normalize, or refine context acquired from disparate sources so that the agent can reason across all the context in a somewhat uniform manner. The underlying work is to make context from all sources (prompts, RAG, memory, etc.), all consumable by the agent as efficiently as possible.

- Context generation - If context processing is about making retrieved context usable to the agent, then context generation gives the agent the outreach to request and receive that additional contextual information at will, but also with constraints.

The various ephemera of LLM chat applications map directly (and sometimes in overlapping ways) to those high-level functions of context engineering:

- Instructions / system prompt - Prompts are the scaffolding for how the generative (or agentic) AI activity will direct its thinking towards accomplishing the user’s goal. Prompts are context in their own right; they aren’t just tonal instructions — they also frequently include task execution logic and rules for things like “thinking step by step” or “take a deep breath” before responding to validate the answer fully addresses the user’s request. Recent testing has shown markup languages are very effective at framing the different parts of a prompt, but care should also be taken to calibrate the instructions to a sweet spot between too vague and too specific; we want to give enough instruction for the LLM to find the right context, but not be so prescriptive that it misses unexpected insights.

- Short-term memory (state/history) - Short-term memory is essentially the chat session interactions between the user and the LLM. These are useful in refining context in live sessions, and can be saved for future retrieval and continuation.

- Long-Term Memory - Long-term memory should consist of information that is useful across multiple sessions. And it’s not just domain-specific knowledge bases accessed through RAG; recent research uses the outcomes from previous agentic/generative AI requests to learn and reference within current agentic interactions. Some of the most interesting innovations in the long-term memory space are related to adjusting how state is stored and linked-to so that agents can pick up where they left off.

- Structured output - Cognition requires effort, so it’s probably no surprise that even with reasoning capabilities, LLMs (just like humans) want to expend less effort when thinking, and in the absence of a defined API or protocol, having a map (a schema) for how to read data returned from a tool call is extremely helpful. The inclusion of Structured Outputs as part of the agentic framework helps to make these machine-to-machine interactions faster and more reliable, with less thinking-driven parsing needed.

- Available tools - Tools can do all sorts of things, from gathering additional information (e.g., issuing RAG queries to enterprise data repositories, or through online APIs) to performing automated actions on behalf of the agent (like booking a hotel room based on the criteria of the request from the agent). Tools could also be sub-agents with their own agentic processing chains.

- Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) - I really like the description of RAG as “dynamic knowledge integration.” As described earlier, RAG is the technique for providing the additional information the LLM didn’t have access to when it was trained, or it’s a reiteration of the ideas we think are most important to get the right answer — the one that’s most relevant to our subjective query.

Phenomenal cosmic power, itty bitty living space!

Agentic AI has so many fascinating and exciting new realms to explore! There are still lots of the old traditional data retrieval and processing problems to solve, but also brand new classes of challenges that are only now being exposed to the light of day in the new age of LLMs. Many of the immediate issues we’re grappling with today are related to context engineering, about getting LLMs the additional contextual information they need without overwhelming their limited working memory space.

The flexibility of semi-autonomous agents that have access to an array of tools (and other agents) gives rise to so many new ideas for implementing AI, it’s hard to fathom the different ways we might put the pieces together. Most of the current research falls into the field of context engineering and is focused on building memory management structures that can handle and track larger amounts of context — that’s because the deep-thinking problems we really want LLMs to solve present increased complexity and longer-running, multi-phased thinking steps where remembering is extremely important.

A lot of the ongoing experimentation in the field is trying to find the optimal task management and tool configurations to feed the agentic maw. Each tool call in an agent’s reasoning chain incurs cumulative cost, both in terms of compute to perform that tool’s function as well as the impact to the limited context window. Some of the latest techniques to manage context for LLM agents have caused unintended chain effects like “context collapse” where compressing/summarizing accumulated context for long-running tasks gets too lossy. The desired outcome is tools that return succinct and accurate context, without extraneous information bleeding into the precious context window memory space.

So many/too many possibilities

We want separation of duties with flexibility to reuse tools/components, so it makes complete sense to create dedicated agentic tools for connecting to specific data sources — each tool can specialize in querying one type of repository, one type of data stream, or even one use case. But beware: in the drive to save time/money/prove something is possible there’s going to be a strong temptation to use LLMs as a federation tool… Try not to, we’ve been down that road before! Federated query acts like a “universal translator” that converts an incoming query into the syntax that the remote repository understands, and then has to somehow rationalize the results from multiple sources into a coherent response. Federation as a technique works okay at small scales, but at large scales and especially when data is multimodal, federation tries to bridge gaps that are just too wide.

In the agentic world, the agent would be the federator and the tools (through MCP) would be the manually-defined connections to disparate resources. Using dedicated tools to reach out across unconnected data sources might seem like a powerful new way to dynamically unite different data streams on a per query basis, but using tools to ask the same question to multiple sources will likely end up causing more issues than it solves. Each of those data sources are likely different types of repositories underneath, each with their own capabilities for retrieving, ranking, and securing the data within them. Those variances or “impedance mis-matches” between repositories add to the processing load, of course. They also potentially introduce conflicting information or signals, where something as seemingly innocuous as a scoring misalignment could wildly throw off the importance given to a bit of returned context, and affect the relevance of the generated response in the end.

Context switching is hard for computers, too

When you send an agent out on a mission, often their first task is to find all relevant data it has access to. Just as it is with humans if each data source the agent connects to replies with dissimilar and disaggregated responses, there will be cognitive load (though not exactly the same kind) associated with extracting the salient contextual bits from the retrieved content. That takes time/compute, and each little bit adds up in the agentic logic chain. This leads to the conclusion that, just like what’s being discussed for MCP, most agentic tools should instead behave more like APIs — isolated functions with known inputs and outputs, tuned to support the needs of different kinds of agents. Heck, we’re even realizing that LLMs need context for context — they do much better at connecting the semantic dots, especially when it’s a task like translating natural language into structured syntax, when they have a schema to refer to (RTFM indeed!).

7th inning stretch!

Now we’ve covered the impact LLMs have had on retrieving and querying for data, as well as how the chat window is maturing into the agentic AI experience. Let’s put the two topics together and see how we can use our newfangled search and retrieval capabilities to improve our results in context engineering. Onwards to Part III: The power of hybrid search in context engineering!