Elasticsearch is packed with new features to help you build the best search solutions for your use case. Learn how to put them into action in our hands-on webinar on building a modern Search AI experience. You can also start a free cloud trial or try Elastic on your local machine now.

Our brand new agentic AI world

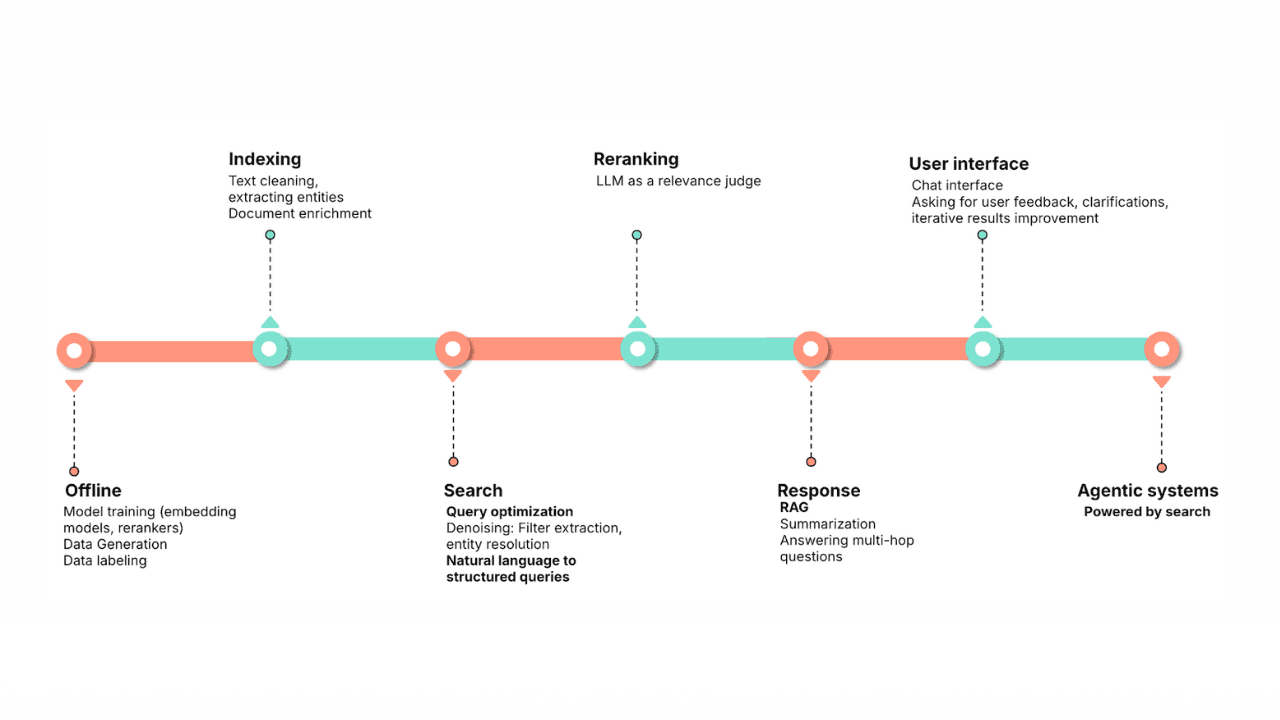

Like many of us, I find myself both giddy and astonished at the pace that AI capabilities are evolving. We first saw large language models (LLMs) and vector search launch us into the semantic revolution where we were no longer hunting and pecking with keywords to find things. Then LLMs showed us new ways of interacting with our data, using chat interfaces to transform natural language requests into responses that distill vast knowledge bases into easily consumable summaries. We now (already!) have the beginnings of automated LLM-driven logic in the form of “agentic AI” workflows that can semantically understand an incoming request, reason about the steps to take, and then choose from the tools available to iteratively execute actions to achieve those goals.

The promise of agentic AI is forcing us to evolve from primarily using ‘prompt engineering’ to shape our generative AI interactions, to focusing on how we can help agentic tools obtain the most relevant and efficient additional information the LLM needs to consider when generating its responses — ‘context engineering’ is the next frontier. Hybrid search is by far the most powerful and flexible means to surface relevant context, and Elastic’s Search AI platform opens up a whole new way to leverage data in service to context engineering. In this article, we’re going to discuss how LLMs have changed the world of information retrieval from two angles, and then discuss how they can work together for greater results. There’s quite a lot of ground to cover…

Part I: How LLMs have changed search

Let’s start from the angle of how LLMs have changed the ways we access and retrieve information.

Our lexical legacy

We’ve all been living in the somewhat limited lexical search world (pretty well, as best we can) for a long time. Search is the first tool we reach for whenever researching or beginning a new project, and up until recently, it was up to us to word our queries in a way that a lexical search engine understands. Lexical search relies on matching some form of query terms to keywords found in a document corpus — regardless of whether the content is unstructured or structured. For a lexical search to return a document as a hit, it has to have matched on that keyword (or had a controlled vocabulary like a synonym list or dictionary to make the conceptual connection for us).

An example lexical multi-match query

At least search engines have the ability to return hits with a relevance score. Search engines provide a wealth of query syntax options to target indexed data effectively and built-in relevance algorithms that score the results relative to the intent of the user’s query syntax. Search engines reap the benefits of decades of advances in relevance ranking algorithms, and that makes them an efficient data retrieval platform that can deliver results scored and sorted by their relevance to the query. Databases and other systems that use SQL as their main method for retrieving data are at a disadvantage here: there is no concept of relevance in a database query; the best they can do is sort results alphabetically or numerically. The good news is you’ll get all the hits (recall) with those keywords, but they’re not necessarily in a helpful order relative to why you were asking for them (precision). That’s an important point, as we’ll see shortly…

Enter the (semantic) dragon

The potential for vector representations of information as an alternative to keyword search has been researched for quite a long time. Vectors hold a lot of promise because they get us out of the keyword-only mode of matching content — because they’re numeric representations of terms and weights, vectors allow concepts to be mathematically close based on a language model’s understanding of how terms relate to each other in the training domain. The long delay for general- purpose vector search was due to models being mostly limited to specific domains, they simply weren’t large enough to sufficiently understand the many different concepts a term might represent within different contexts.

It wasn’t until Large Language Models (LLMs) came along a few years ago with their ability to train on much larger amounts of data (using transformers and attention) that vector search became practical — the size and depth of LLMs finally allowed vectors to store enough nuance for them to actually capture semantic meaning. That sudden increase in the depth of understanding allowed LLMs to now serve a large number of natural language processing (NLP) functions that were previously locked, perhaps the most impactful being the ability to infer the most likely next term in a sequence given the context of what’s in the sequence so far. Inference is the process that gives generative AI its near-human ability to produce text. AI-generated text is informed by the LLM’s understanding of how terms are related within its training data and also uses the phrasing of the request to disambiguate between different contexts the terms might appear in.

As magical as generative AI is, there are limitations to LLMs that cause errors in quality and accuracy, commonly called hallucinations. Hallucinations occur when the LLM doesn’t have access to the information (or isn’t guided to the correct context) to base its answer in truth so, being helpful, it will instead generate a confident and plausible-sounding response that’s made up. Part of the cause is that while LLMs learn the usage of language within large domains of diverse information, they have to stop training at a certain point in time, so there’s a timeliness factor to their understanding — meaning that the model can only know what was accurate up to the time it stopped training. Another factor for hallucinations is that the model usually doesn’t know about privately held data (data not available on the public internet), and that’s especially significant when that data contains specific terms and nomenclature.

Vector databases

LLMs vectorize content to its model space using a technique called text embedding, which refers to embedding or mapping the content’s semantic meaning within the model’s world view based on the training it received. There are a few steps involved to prepare and process content for embedding, including chunking and tokenization (and subword tokenization). The result is typically a set of dense vectors representing the model’s understanding of that chunk of content’s meaning within its vector space. Chunking is an inexact process that’s meant to fit content into the limitations of a model’s processing constraints for generating embeddings, while also attempting to group related text into a chunk using semantic constructs like sentence and paragraph indicators.

The need for chunking can create a bit of semantic lossiness in an embedded document because individual chunks aren’t fully associated with other chunks from the same document. The inherent opaqueness of neural networks can make this lossiness worse — an LLM is truly a “black box” where the connections between terms and concepts made during training are non-deterministic and not interpretable by humans. This leads to issues with explainability, repeatability, unconscious bias, and potentially a loss of trust and accuracy. Still, the ability to semantically connect ideas, to not be tied to specific keywords when querying is extremely powerful:

An example semantic query

There’s one more issue to consider for vector databases: they’re not search engines, they’re databases! When a vector similarity search is performed, the query terms are encoded to find a set of (embedding) coordinates within the model’s vector space. Those coordinates are then used as the bullseye to find the documents that are the “nearest neighbors” to the bullseye — meaning a document’s rank (or placement in the results) is determined by the calculated similarity distance of that document’s coordinates from the query’s coordinates. In which direction should ranking take precedence, which of the possible contexts is closest to the user’s intent? The image I liken it to is a scene from the movie Stargate, where we have the six coordinate points that intersect to tell us the destination (the bullseye) but we can’t get there without knowing the “7th symbol” - the coordinates of the starting point representing the user’s subjective intention. So rather than the relative ranking of vectors being based on an ever-expanding and undifferentiated sphere of similarity, by considering the subjective intent of the query through expressive syntax and relevance scoring, we can instead get something resembling a cylinder of graduated subjective relevance.

The inference capabilities of an LLM might help identify the most probable context it has for the query, but the problem is that without help, the incoming query’s coordinates can only be determined by how the model was originally trained.

In some ways you could say vector similarity goes to the opposite extreme from a strictly keyword match — its strength lies in its ability to overcome the issues of term mismatch, but almost to a fault: LLMs tend towards unifying related concepts rather than differentiating between them. Vector similarity improves our ability to match content semantically, but doesn’t guarantee precision because it can overlook exact keywords and specific details that aren’t disambiguated enough by the model. Vector similarity search is powerful in itself, but we need ways to correlate the results we retrieve from a vector database with results from other retrieval methods.

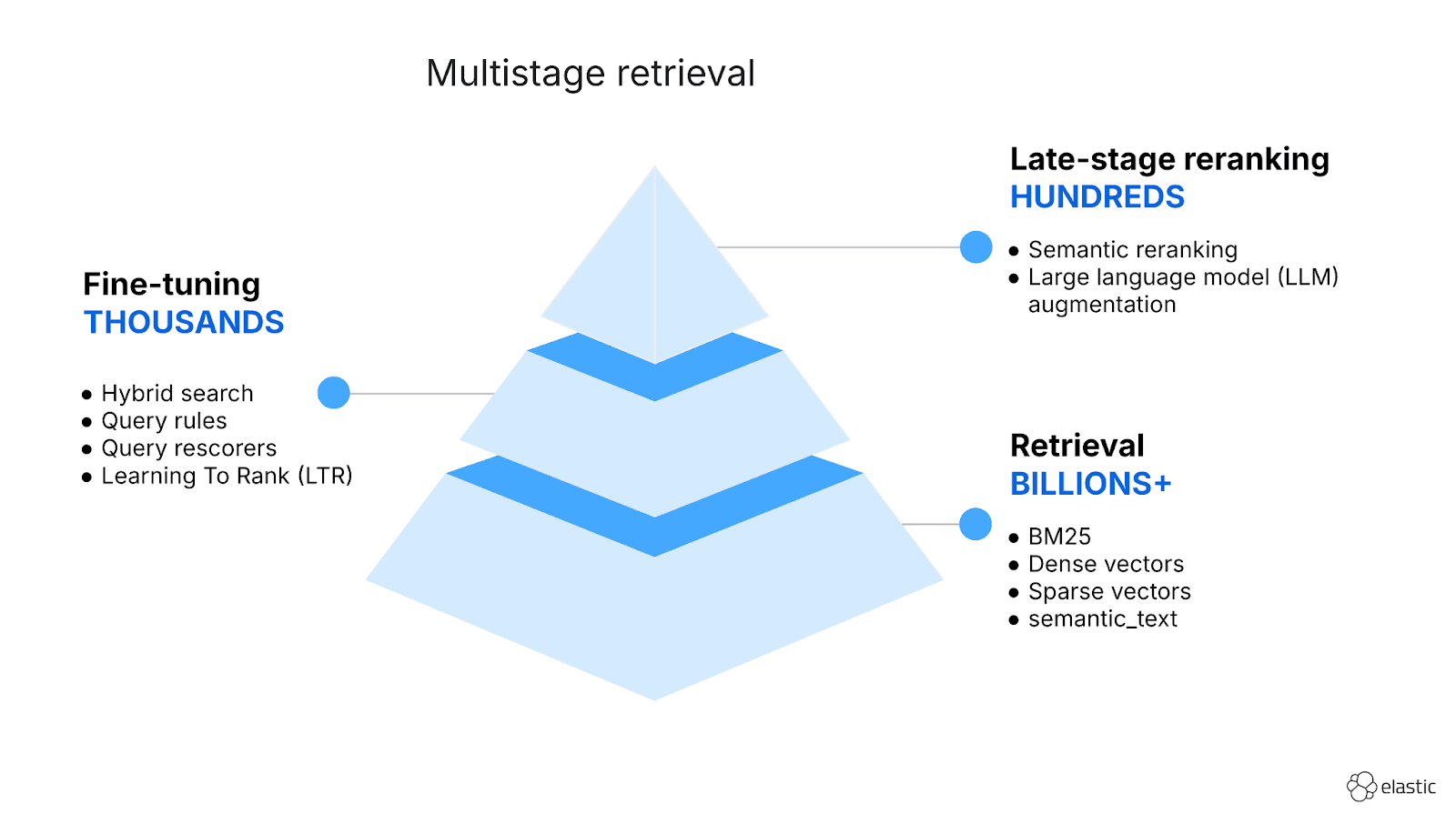

Reranking techniques

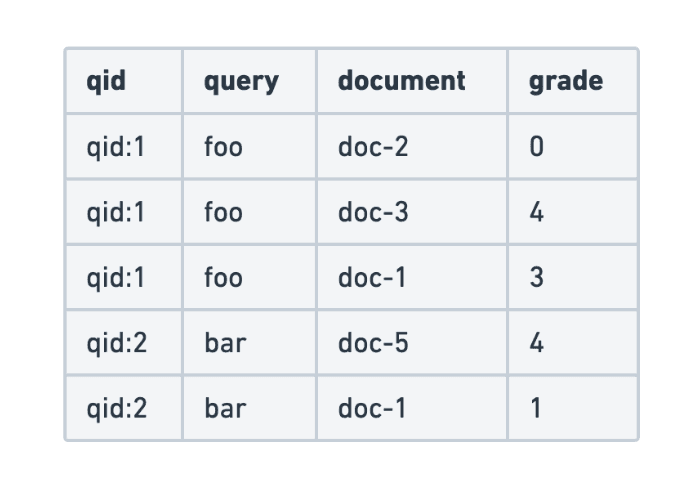

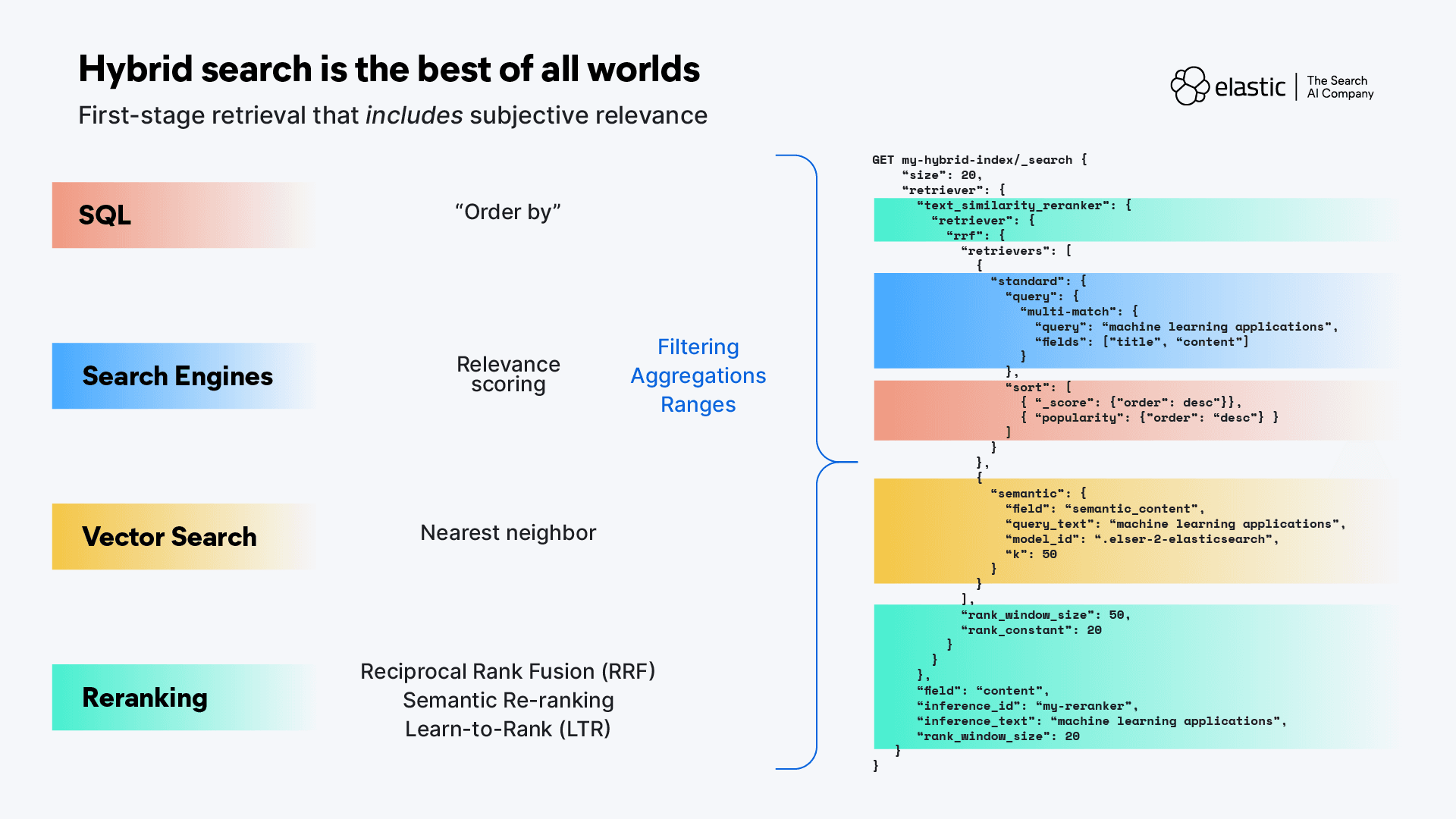

Now is a good time to mention a general technique called reranking, which re-scores or normalizes result sets to a unified rank order. The need for reranking could be due to results from multiple sources or retrieval methods having different ranking/scoring mechanisms (or none at all, SQL!), or re-ranking could be used to align the results from non-semantic sources to the user’s query semantically. Reranking is a second-stage operation, meaning a set of results that have been collected by some initial retrieval method (i.e. SQL, lexical search, vector search) are then reordered with a different scoring method.

There are several approaches available, including Learning-To-Rank (LTR) and Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) — LTR is useful for capturing search result features (likes, ratings, clicks, etc.) and using those to score and boost or bias results. RRF is perfect for merging results returned from different query modalities (e.g. lexical and vector database searches) together into a single result list. Elastic also provides the flexibility to adjust scores using linear reranking methods.

One of the most effective reranking techniques however is semantic reranking, which uses an LLM’s semantic understanding to analyze the vector embeddings of both the query and results together, and then apply relevance scoring/rescoring to determine the final order. Semantic reranking requires a connection to a reranking model, of course, and Elasticsearch provides an Inference API that lets you create rerank endpoints that leverage built-in models (Elastic Rerank), imported third-party models, or externally-hosted services like Cohere or Google Vertex AI. You can then perform reranking through the retriever query abstraction syntax:

An example multi-stage retriever reranking operation

Sounds great, right? We can perform reranking on results from disparate sources and get close to a semantic understanding of all types of content… Semantic reranking can be expensive both computationally as well as in processing time required, and because of that, semantic reranking can only feasibly be done on a limited number of results, which means that how those initial results get retrieved is important.

The context retrieval method matters

Subjective intent is an important factor in determining the accuracy of a result, in scoring its relevance. Without the ability to consider the user’s intent for performing the query (as expressed through flexible syntax, or by second-stage reranking), we can only select from the existing contexts already encoded within the model space. The way we typically address this lack of context is through techniques like Retrieval Augment Generation (RAG). The way RAG works is it effectively shifts the query’s coordinates by including additional related terms returned from a pre-query for contextually relevant data. That makes the engine providing that additional context and its initial method for performing retrieval all the more important to the accuracy of the context!

Let’s review the different context retrieval methods and how they can help or hurt a RAG operation:

- Hybrid search retrieval without a search engine still lacks subjective relevance. If the platform providing RAG is primarily SQL-based underneath (which includes most “data lake” platforms), it’s lacking relevance scoring at the initial retrieval stage. Many data lake platforms provide their own version of hybrid retrieval (not search), usually combining reranking techniques like semantic reranking and RRF on their SQL-based retrieval and vector database results. A simple sort is obviously insufficient for subjective ranking, but even when used as the basis for a second-stage semantic reranking operation, SQL as the first-stage retrieval becomes a problem when the semantic reranking is performed only on the “top k” hits — without some way to score results at retrieval, what guarantee do we have that the best results are actually in the top results?

- Vector similarity alone isn’t good enough for RAG. It’s really due to a compounding set of issues - it’s the lossiness of embedding, along with naive chunking methods, with how similarity is calculated, and the crucial missing component of subjective intent. One of the main goals of RAG is to ground generative AI interactions in objective truth, both to prevent hallucinations as well as to inform the LLM about the private information it had no knowledge of during training. We can use the additional context provided through RAG to constrain and direct LLMs to consider the connections and details we know are most important to answering the question at hand. To do that, we need to use both semantic and lexical approaches.

- File-based grep/regex RAG. There are some quarters of the agentic AI universe pointing to the use of vastly enlarged context windows that access local files via grep and regex for RAG rather than external retrieval platforms. The idea is that with a much larger context window available, LLMs will be able to make conceptual connections within their own thinking space rather than relying on chunked bits and pieces and multiple retrieval methods/platforms to collect relevant information. While it’s true in theory that having an entire document delivers a fuller picture than document segments, this can only work in small data domains (or, for example, when supplying files for vibecoding), and even then, the initial retrieval method is a scan of all documents with a keyword-only match.

Search is more than retrieval

Search engines are purpose-built for making queries as fast and flexible as possible. Internally, they utilize specialized data structures for storing and retrieving different kinds of data in ways that cater to those data types. Elasticsearch provides optimized storing and querying of essentially all types of data, including unstructured/full-text lexical search (match, phrase, proximity, multi-match), fast keyword (exact match) matching and filtering, numeric ranges, dates, IP addresses, and is very flexible in how it stores document structures (e.g. nested or flattened docs). Elasticsearch is also a native vector database that can store and query both sparse and dense vector types, and we continue to explore innovative ways (for example, Better Binary Quantization (BBQ) & DiskBBQ) to maintain search fidelity while improving the speed, scalability, and costs associated with vectorized content. The Elasticsearch platform also provides built-in data resilience and high-availability, and includes data lifecycle management capabilities such as Searchable Snapshots that allow you to keep infrequently-accessed or long-term retention data on cost-effective object storage — but still fully searchable.

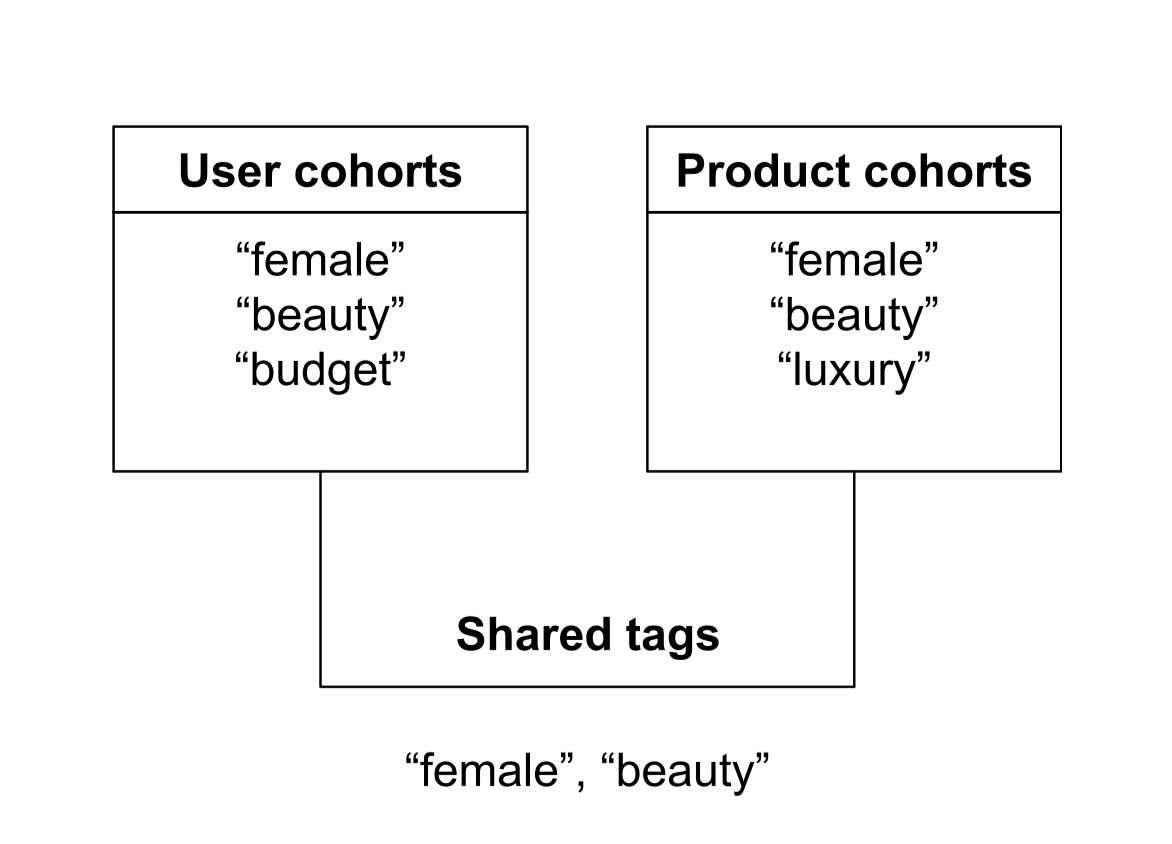

Hybrid search is the best of all worlds

Hybrid search (not just hybrid retrieval!) combines the strengths of traditional lexical search with the semantic understanding of LLMs and vector similarity search. This synergy allows for targeting highly relevant results at the retrieval stage through any of the flexible query syntax options a search engine provides: intent-driven syntax options and relevance scoring, multi-modal data retrieval, filtering, aggregations, and biasing. With search syntax like ES|QL and multi-stage retrievers, we can flexibly combine traditional search with semantic search, filters, and multiple reranking techniques all in one request.

One of the biggest benefits of hybrid search is that your queries can use specialized syntax for multiple different data types simultaneously. Those different query syntaxes can be used not just for finding results, they can also be used as filters or aggregations on the results. For example, one of the most common query types that frequently gets combined with other syntax is geospatial analysis. You can do things like query for results that have geo coordinates within a specified distance of a point, or request aggregations on your results by region, or aggregations to track and alert on movements into/out of a zone. With hybrid search you have the flexibility to combine syntaxes to target results in the most accurate way, to retrieve the content closest to your context.

Intermission

This first part tells the story of how vector search has changed the way we’re able to retrieve data, and sets the stage for the changes LLMs have brought to the query mechanisms we use to interact with data. We’re going to pretend we had to break this up into multiple parts so that LLMs could understand it without losing context… ;-) Let’s learn more about why that's important in Part II: Agentic AI and the need for context engineering, and in Part III, we’ll return to our discussion of hybrid search.